Black Excellence Personified

Remembering Black Wall Street

The rich tapestry of American Blackness is organized around our fight for the right to exist. This struggle is inextricably linked with our ability to accumulate wealth unencumbered.

One such pursuit of freedom and economic opportunity was the migration of freed slaves from the South after slavery was abolished in 1865. Many travelled west to escape the spreading racial violence and debilitating political repression, drawn by the promises of all-Black towns, safe havens to pursue self-sufficiency.

Nowhere in the country was the proliferation of these communities more widespread than in Oklahoma, where 50 all-Black towns and settlements were established in the 65 years following emancipation. One of these towns was Greenwood, a flourishing community that would eventually become known as “Black Wall Street” while also serving as one of the most deadly and destructive reminders of our country’s legacy of racial violence and repression.

“We are used to the shedding of innocent blood, and the heart of this nation is torpid, if not dead, to the national claims of justice and humanity, where the victims are of the colored race.”

– Frederick Douglas, 1886

A Dusty Town by the Tracks

In 1906, O.W. Gurley, a wealthy Black land speculator born to enslaved parents in Alabama, bought 40 acres of land on the outskirts of Tulsa, founding Greenwood the year before Jim Crow laws began to legally enforce segregation in Oklahoma.

Over the next 15 years, amid growing racial tensions in the state, Gurley shepherded Greenwood’s growth from a rooming house on a dusty trail along the train tracks into one of the most prosperous Black urban communities in the country. By 1921, Greenwood offered refuge to 10,000 Black residents, many of them sharecroppers who had fled the South and descendants of enslaved peoples who walked the Trail of Tears alongside the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole tribes.

Greenwood also had schools, churches, and over 100 Black-owned businesses – banks, grocery stores newspapers and more – with offices filled by dozens of professionals from physicians to attorneys. Greenwood even had an unemployment agency that helped Black men find work.

The town’s success at generating wealth and keeping it in the community led to luxuries like indoor plumbing and superior schools, which fueled resentment among Greenwood’s lesser-off white neighbors.

The success of Greenwood was an intentional act of solidarity by Black people looking to escape oppression and create the American Dream for themselves and future generations. Many of Tulsa’s white residents saw this as an act of defiance and spurned the community, which they stereotyped as violent and decadent. Black people were seen as criminals out to harm the white folks in neighboring towns.

In May of 1921, the tensions reached a tipping point when Dick Rowland, a Black 19-year-old, took a break from his job shining shoes to use the “Colored” restroom. This required a trip to another building and an elevator ride to the top floor. Riding alongside him was Sarah Page, the white 17-year-old elevator operator. Exactly what happened next may never be known, but what started as a misunderstanding or argument soon grew into an allegation of rape against Rowland, who was arrested the next day on a charge he would later be exonerated for.

However, stoked by inflammatory news reports, a white mob quickly formed at the courthouse threatening to lynch Rowland. When a group of around 75 armed Black men, many of them , went to the courthouse that night to try and protect Rowland they were met by a growing mob more than 2,000 strong. Hurling a slur toward one of the Black veterans, a white man demanded he hand over his gun and when he was rebuffed, he attempted to disarm the veteran. A shot rang out and one of America’s most devastating racial assaults began.

As the Black men fled back to Greenwood, white vigilantes pursued them, around 400 of whom were deputized and armed by Tulsa police as others looted guns and ammunition from stores in the heart of the Black business district in preparation for the coming attacks.

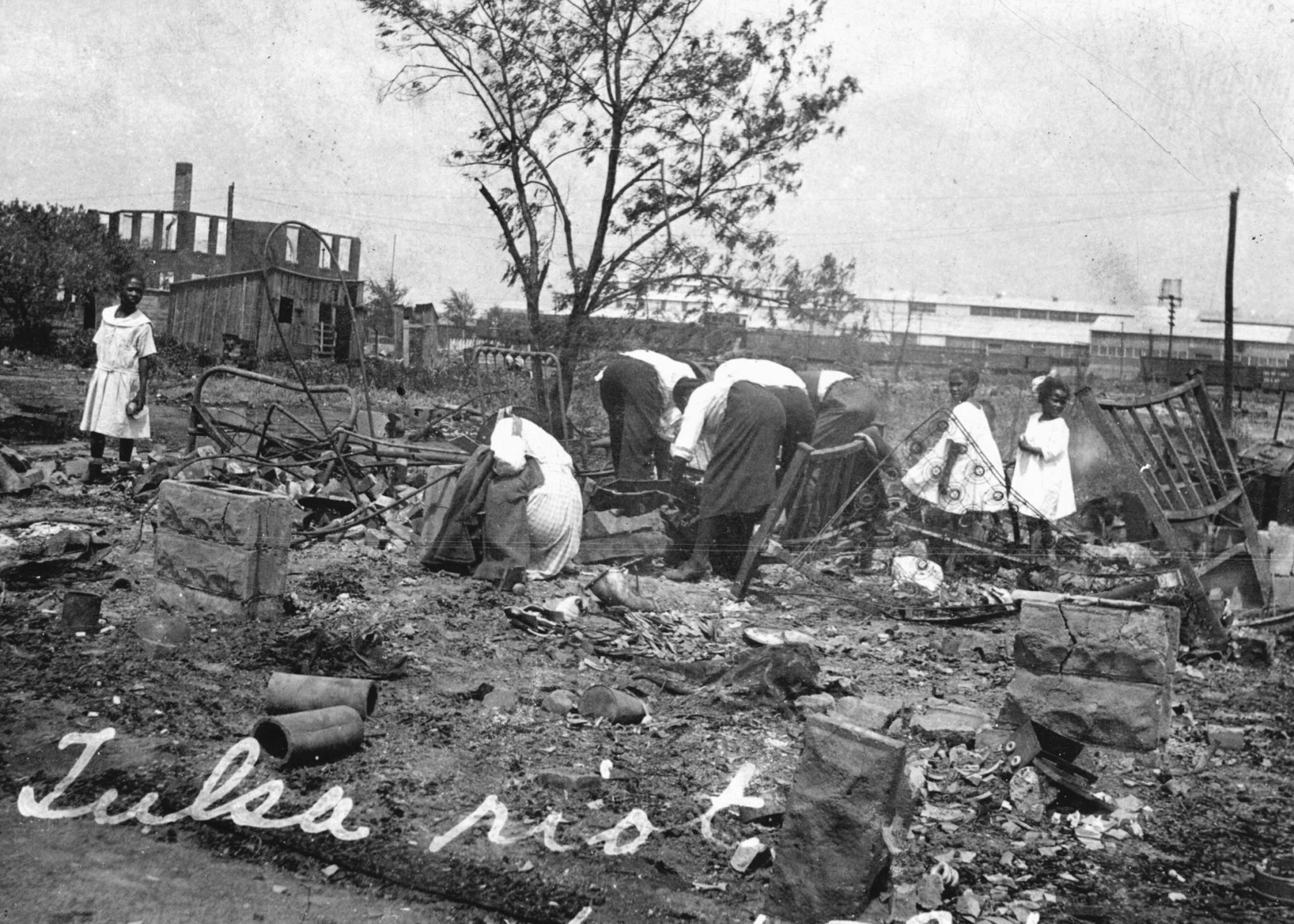

The events of the next 18 hours would leave as many as 300 residents of Greenwood dead and more than 800 injured while the Oklahoma National Guard looked the other way as mobs moved through the town looting and destroying homes and businesses. The Black residents of Greenwood unsuccessfully tried to mount a defense as over 1,000 homes were burned to the ground, along with nearly every other building in the town, from businesses to schools, churches, a library and even a hospital.

During the attacks authorities detained 6,000 Black residents, marching some through the streets at gunpoint as their white neighbors cheered on. As the fires died down and violence came to an end, men, women and children lay dead in the charred ruins of Greenwood, eventually to be buried in mass graves or dumped into the Arkansas river. Days later, the National Guard demanded the men and women they had taken as prisoners begin forced labor, threatening those who refused to work with arrest. In the week following the massacre about half of those arrested had won their freedom, but when they made their way back to Greenwood, it was gone.

At the end of the day, 10,000 people – nearly the entire Black population of Tulsa – had been left homeless and destitute.

Following formal investigations, most of the estimated dead have yet to be found as many of the records were destroyed or suppressed.

Insurance companies classified the slaughter as a “riot” instead of a coordinated attack, enabling them to deny more than $200 million in claims in today’s dollars. Many families didn’t trust banks and kept their money at their homes, losing entire life savings to looters and fire.

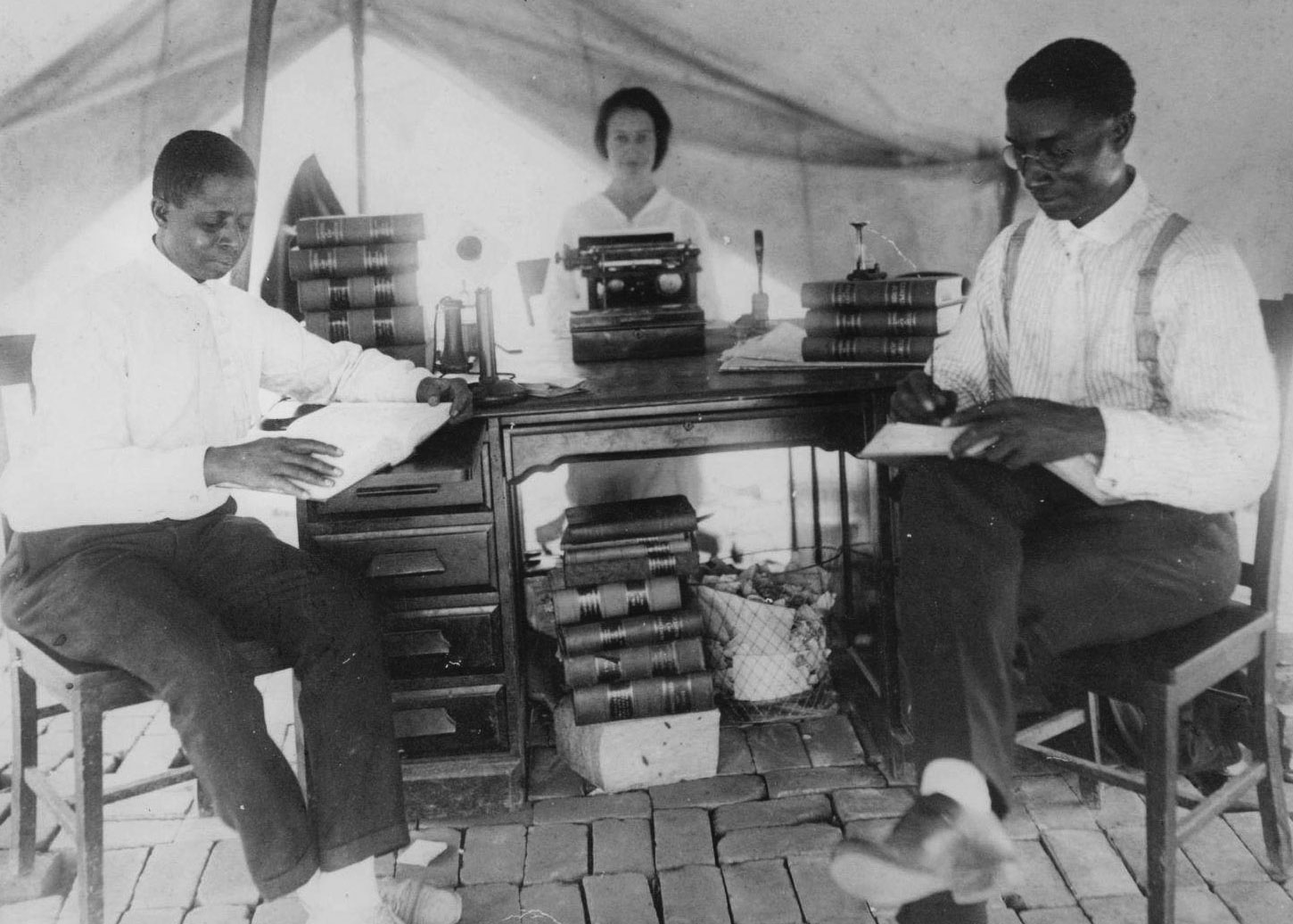

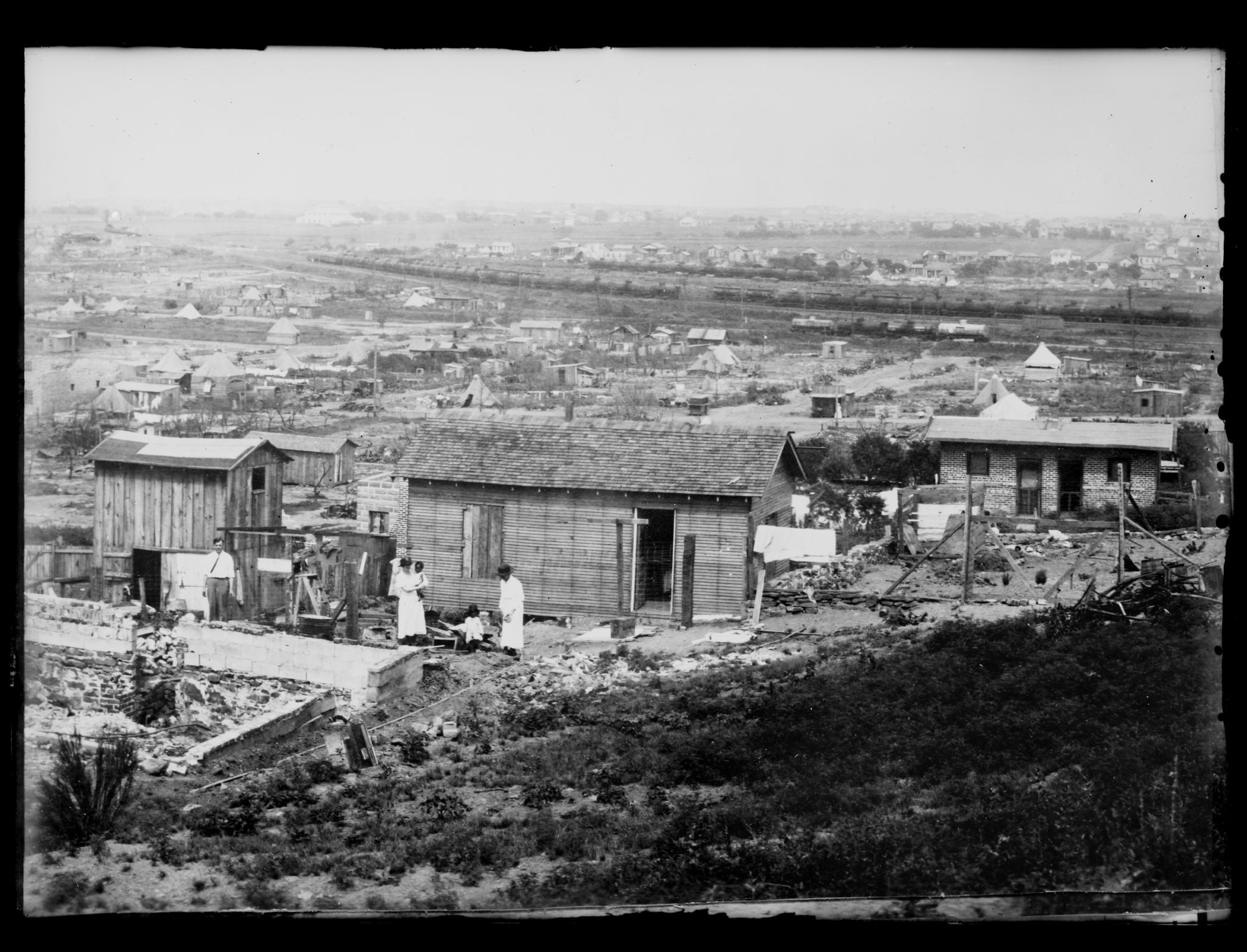

The residents of Greenwood were left to rebuild on their own, often under the cover of darkness in defiance of city officials who hastily rezoned Greenwood as industrial land and put in place strict building codes intended as insurmountable hurdles to reconstruction.

It wasn’t until a Greenwood attorney, B.C. Franklin, sued the City of Tulsa that officials relented and allowed the rebuilding to continue unobstructed.

Nonetheless, Greenwood was reborn. It was this new Greenwood – a flourishing community striving to overcome tragedy – that began drawing comparisons to Wall Street.

But, Black Wall Street, unlike the Wall Street more than a thousand miles away, didn’t rise to prominence profiting from human bondage. Black Wall Street rose from the ashes left by hate and racism to defy subjugation and create a community where Black excellence and autonomy could be celebrated, supported and perpetuated.

Greenwood enjoyed 50 years of prosperity, which was brought to an abrupt halt by a seemingly innocuous law that would go on to decimate and divide Black communities across the country: the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956.

Footage from Greenwood filmed years after the massacre.

A Road Runs Through It

How the Federal Aid Highway Act Reshaped Greenwood

Congress’s allocation of $26 billion for the Federal Aid Highway Act funded a 41,000-mile network of interstate highways that not only facilitated white flight to the suburbs, but resulted in minoritized communities – primarily Black neighborhoods – being destroyed, often under the guise of “slum removal.”

“In states around the country, highways disproportionately displaced Black households and cut the heart and soul out of thriving Black communities as homes, churches, schools and businesses were destroyed,” writes NYU School of law professor Deborah Archer in ‘White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes’: Advancing Racial Equity Through Highway Reconstruction.

As legal and political battles over housing discrimination, poverty alleviation and economic policy were being waged, “Highways were built through and around Black communities to physically entrench racial inequality and protect white spaces and privilege,” Archer writes. “The physical boundaries they created would become permanent tools of white supremacy, boundaries that could withstand the evolution of civil rights laws. Rather than be forced to comply with the law, the highways were the law.”

The physical force that would finally cut Greenwood into pieces was completed in 1971 when four highways circling Tulsa’s downtown converged on the community, severing its main business thoroughfare, displacing residents and depressing home values for those who remained.

A “Black Wall Street” mural decorates a section of Interstate 224, one of the highways that cut through the heart of Greenwood.

Although the legacy of Greenwood may seem like a distant memory, the lessons we can draw from its story are as relevant as ever.

The challenges and their ripple effects that were put in front of the residents of Black Wall Street as they tried to accumulate wealth, haven’t gone away. The typical Black household in the Tulsa metropolitan area has only six cents of wealth for every one dollar of the typical white household.

Nationally, the gap between median Black and white household wealth – a measure of all assets minus liabilities – is as stark as it was in 1968, when the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated and the Civil Rights Act of 1968 passed. In 2019, the typical white family owned $184,000 in wealth compared to a typical Black family with $23,000 of wealth.

The Fight for Justice Goes On

For decades there were no public ceremonies, memorials or any efforts to commemorate the events that led to a prosperous town be burned to the ground. Many people didn’t want to face the trauma and the role it still plays in the experience of Tulsa’s Black community. Even into 2022, Tulsa is still coming to terms with the destruction of Greenwood.

Along with other survivors, Viola Fletcher, now 107, testified on May 19, 2021 asking Congress for justice on behalf of her family and so many others who were killed, or whose homes or businesses were destroyed on that day. They’ve waited 100 years to be fully heard and have their calls for justice answered.

Let us never forget that Black Wall Street existed and was destroyed because it threatened the power structures of its time. As we celebrate Black resilience, Black innovation and Black excellence, let us not forget the children of the formerly enslaved who came together as a community and created their oasis. Let us never forget the power of Black ingenuity and let us never forget the souls lost during the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

Posted by CNN Politics on Wednesday, May 19, 2021

Why It Matters

At the College of Business, my role as an intersectional leader and champion of diversity, equity and inclusion has a lot to do with storytelling.

My job is not to persuade you of my point of view, it’s only to give you a different perspective. My job is to encourage storytelling that helps us all question our preconceptions and connect with one another in order to make informed decisions about the way we want to live our lives. When you give someone the full story, you can hold them accountable.

The better we can relate to people who are different from us, whose histories and experiences hold compelling stories full of insights we have yet to hear, the greater the change will be that we can make together. To be an ethical business leader, you need to seek out those stories and work to understand the historical, economic and social contexts in which business operates.

As our College embarks on the collective journey of using Business for a Better World, we need to have an understanding of the world around us in order to change it.

About CSU’s College of Business

The College of Business at Colorado State University is focused on using business to create a better world.

As an AACSB-accredited business school, the College is among the top five percent of business colleges worldwide, providing programs and career support services to more than 2,500 undergraduate and 1,300 graduate students. Faculty help students across our top-ranked on-campus and online programs develop the knowledge, skills and values to navigate a rapidly evolving business world and address global challenges with sustainable business solutions. Our students are known for their creativity, work ethic and resilience—resulting in an undergraduate job offer and placement rate of over 90% within 90 days of graduation.

The College’s highly ranked programs include its Online MBA, which has been ranked the No. 1 program in Colorado by U.S. News and World Report for five years running, and the Impact MBA, recognized by Corporate Knights as a Top 20 “Better World MBA” worldwide.