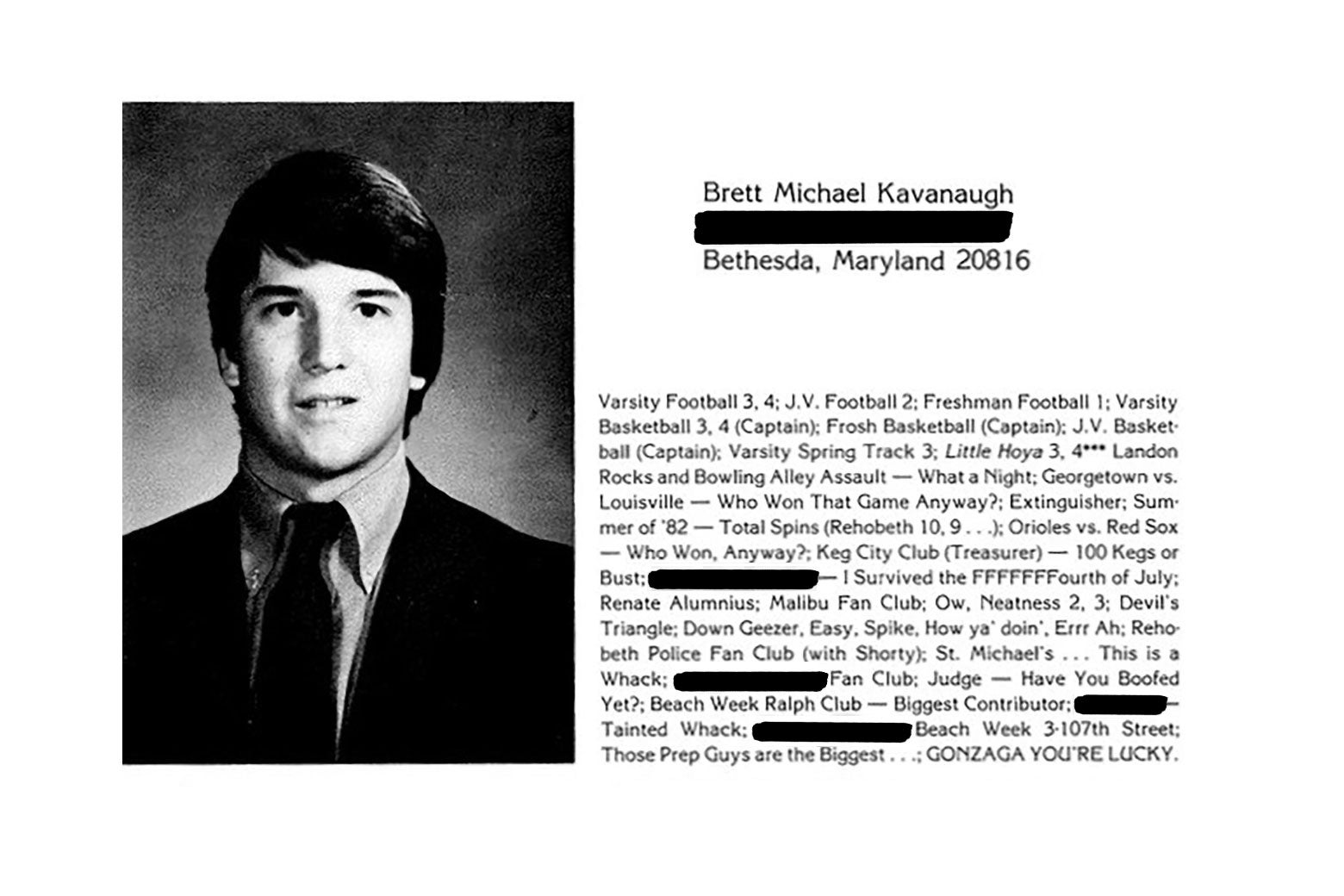

For what it’s worth, and absent evidence or allegations to the contrary, I believe Brett Kavanaugh’s claim that he was a virgin through his teens. I believe it in part because it squares with some of the oddities I’ve had a hard time understanding about his alleged behavior: namely, that both allegations are strikingly different from other high-profile stories the past year, most of which feature a man and a woman alone. And yet both the Kavanaugh accusations share certain features: There is no penetrative sex, there are always male onlookers, and, most importantly, there’s laughter. In each case the other men—not the woman—seem to be Kavanaugh’s true intended audience. In each story, the cruel and bizarre act the woman describes—restraining Christine Blasey Ford and attempting to remove her clothes in her allegation, and in Deborah Ramirez’s, putting his penis in front of her face—seems to have been done in the clumsy and even manic pursuit of male approval. Even Kavanaugh’s now-notorious yearbook page, with its references to the “100 kegs or bust” and the like, seems less like an honest reflection of a fun guy than a representation of a try-hard willing to say or do anything as long as his bros think he’s cool. In other words: The awful things Kavanaugh allegedly did only imperfectly correlate to the familiar frame of sexual desire run amok; they appear to more easily fit into a different category—a toxic homosociality—that involves males wooing other males over the comedy of being cruel to women.

In both these accounts, Kavanaugh is laughing as he does something to a woman that disturbs or traumatizes her. Ford wrote in her letter to Sen. Dianne Feinstein, “Kavanaugh was on top of me while laughing with [Mark] Judge, who periodically jumped onto Kavanaugh. They both laughed as Kavanaugh tried to disrobe me in their highly inebriated state. With Kavanaugh’s hand over my mouth, I feared he may inadvertently kill me.”

“Brett was laughing,” Ramirez says in her account to the New Yorker. “I can still see his face, and his hips coming forward, like when you pull up your pants.” She recalled another male student shouting about the incident. “Somebody yelled down the hall, ‘Brett Kavanaugh just put his penis in Debbie’s face,’ ” she said.

If these allegations are true, one of the more shocking things about them is the extent to which the woman being mistreated exists in a room where the men are performing for each other—using the woman to firm up their own bond. The Kavanaugh yearbook is littered with dumb codes that seem to speak to exactly this tendency—stuff like “boofing” and “devil’s triangle” all suggest that what mattered to Kavanaugh was displaying club membership. The question is: At whose expense?

It goes without saying, I hope, that virgins are perfectly capable of doing everything Kavanaugh has so far been accused of. Offering a detail that personal was not only meant to be exculpatory in a specific sense; it was also deployed to counter an emerging image of Kavanaugh as a sleazy frat guy like his close friend and classmate Mark Judge. But he overshot the mark. If you’re going by his reactions in the Fox News interview, Kavanaugh’s wounded astonishment at the very existence of bad behavior would mean he couldn’t have known his good friend Mark Judge, who has written plenty about his own, very well at all. Kavanaugh’s strategy, in other words, was to present himself as all innocence: not just a virgin, but a virgin who’s never even heard of—let alone done!—some of the things he’s accused of. Everyone says so: “The women I knew in college and the men I knew in college said that it’s inconceivable that I could’ve done such a thing,” he said to Fox’s Martha MacCallum of Ramirez’s allegation.

This is an unwise thing to claim; first, because what people say you’re capable of isn’t actually proof of what you did or didn’t do, and second, because it happens to be untrue. One of Kavanaugh’s freshman year roommates, James Roche, expressed precisely the opposite view, saying he found Ramirez’s story credible and recalling that Kavanaugh “was a notably heavy drinker, even by the standards of the time, and that he became excessive and belligerent when he was very drunk.” Another unnamed former classmate in the New Yorker story also used the word belligerent in describing Kavanaugh when inebriated.

One thing we’ve learned about Kavanaugh, then, is that he perpetually overshoots. To put it bluntly, he lies. Rather than admit he was flawed, or made some mistakes he regrets, or simply acknowledge that different people might have seen him differently—as they demonstrably did—he’s doubling down on an unsustainable and untrue account of himself and his reputation. Under immense pressure and a bright spotlight, he claims that “the women I knew in college” and “the men I knew in college” (a large group!) will all vouch for him. This is injudicious. But it adds to an emerging profile of a man who will go to long lengths to get approval. It’s what Kavanaugh did when he accepted the nomination from Trump with a sycophantic speech that has in the months since he made it become a telling document of his exaggerated need to affirm the club he belongs to. He claimed he’d “witnessed firsthand” Trump’s “appreciation for the vital role of the American judiciary,” adding—in a burst of mendacious hyperbole—that “no president has ever consulted more widely or talked with more people from more backgrounds to seek input about a Supreme Court nomination.” And it’s what he did in that Fox interview: present himself as a friendly virgin who worked on school and service projects, and little else.

A man who runs on external approval runs into problems quickly. Kavanaugh’s strategy in the Fox interview was to portray himself as a public-spirited choirboy while sitting next to his kind-looking wife: He repeatedly and proudly referred to the high school friends who “produced overnight 65 women who knew me in high school.” He staked a lot on that letter, whose signatories attested that “he has behaved honorably and treated women with respect.”

Unfortunately for him, one of those much-invoked character witnesses—a woman named Renate Schroeder Dolphin, who offered her name in support of his—recently discovered how he, in turn, had used hers. The New York Times reported that Kavanaugh and a number of other graduates, including eight members of the football team, referred to themselves in the yearbook as “Renate Alumni.” The implication is obvious, and a poem from another guy’s page lays it out clearly: “You need a date/ and it’s getting late/ so don’t hesitate/ to call Renate.” When Kavanaugh included himself in this group in his yearbook page, I think we can all agree that he was neither a) “behaving honorably” as the letter attested, nor b) “treating women with dignity and respect,” as he repeatedly insisted in his Fox interview. This was not “being a good friend.” Much of what Kavanaugh said in that interview was disproved in the same day. This tells us something about how the man responds to incentives. Today, he needs to have been “a good friend” to women to be approved to the Supreme Court. Back then, he needed approval from his buddies, so he helped drag a girl’s name through the mud to get it. Today he needs to have been a virgin. Back then he needed to have slept with Renate. He’ll tell the truth as it needs to be, not as it is.

Many have wondered (purely as a matter of strategy) why Kavanaugh has issued such forceful denials. Most good lawyers would advise against locking oneself in quite so firmly. But one thing that might make a guy overconfident in his ability to bluff his way out is faith in the support of his in-group. It’s Omertà. If you deny wrongdoing as a united front, you’ll get away with it.

That’s where even this dumb yearbook entry thing becomes instructive: Kavanaugh was caught being cruel to a girl, and instead of owning up, he doubled down. It shows how boys who are cruel together lie together. This is why their denials are more emphatic than they need to be; each relies on the strength and intensity of the others. “Judge Kavanaugh and Ms. Dolphin attended one high school event together and shared a brief kiss good night following that event,” read a statement from Kavanaugh’s lawyer (she denies the kiss—I’ll take her word over his). “They had no other such encounter. The language from Judge Kavanaugh’s high school yearbook refers to the fact that he and Ms. Dolphin attended that one high school event together and nothing else.” Yeah, right. Four of the other players depicted in the “Renate alumni” photo issued a statement claiming that the phrase was “intended to allude to innocent dates or dance partners and were generally known within the community of people involved for over 35 years.” Before laughing at the absurdity of this, it’s worth reiterating that Renate did not know. One might then reasonably ask who the phrase “the community of people involved” includes.

How does the yearbook help us understand the other allegations against Kavanaugh? Well, for one thing, Kavanaugh’s admitted virginity shows how empty these rumors about Renate were. Whatever stories they circulated about her sexual behavior weren’t actually about her; to them she was less a person than a token you claim to gain status with your bros. That tells us something valuable about how Kavanaugh was willing to treat women when other guys were around. It also offers a clear window into how male networks like Kavanaugh’s work. If you get caught, you deny, and if you can’t, you manufacture explanations that may sound ridiculous to an outside audience. But you never break. His yearbook buddies tried to shelter him because sheltering him sheltered them.

The fatal flaw in the Republicans’ accusations of “conspiracy” is that if you wanted to falsely accuse someone of sexual misconduct, you’d likely choose something damning and unambiguous. You probably wouldn’t include—as both allegations against Kavanaugh do—witnesses in the room who were his friends. You wouldn’t (in Ramirez’s case) admit to having been drinking. You’d have no memory gaps, express no doubts or confusion, and you’d probably claim to have been raped. Instead, the stories that have arisen so far can only really be corroborated by the perpetrator’s pals.

These male witnesses universally remember nothing. Now, it’s possible they don’t remember because it never happened. Maybe they were too drunk to recall. Or maybe they’re tapping into a long tradition of male in-group protection, partly to avoid being implicated themselves. Mark Judge remembers nothing so much that he’s gone into hiding—his first and only comment to the journalist who tracked him down was, “How did you find me?” The other men Ramirez says were in the room at Yale also have “zero recollection.” It could be there’s just nothing to remember, but there are other possibilities, like a mutually exonerating code of male secrecy. Brett Kavanaugh is on the record instructing his buds to keep Omertà after a 2001 boat trip to Annapolis, Maryland—even from their wives. “Reminders to everyone to be very, very vigilant w/r/t confidentiality on all issues and all fronts, including with spouses,” he wrote after apologizing for a variety of things, including “growing aggressive after blowing still another game of dice.” By this time he wasn’t in high school. He was in the White House.

Previously in Slate: Why Christine Blasey Ford’s allegation has men more afraid than ever.