Amid rows of houses and a sprinkling of bars, coffee shops, convenience stores and restaurants in Riverside, an unpretentious corner of Baltimore, one building stands out: a redbrick townhouse that was once an old church. It is the office of David Simon, a master of the medium of television.

Up three steps and through thick wooden doors is a kitchen displaying posters for Sergio Leone’s C’era una volta in America (Once Upon a Time in America), Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch and Simon’s own series Treme, set in post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans. But it is the bathroom that offers an oblique clue as to where he is off to next: period posters announcing long-ago labour strikes – one by police, another by a newspaper guild.

Simon is animated by the perpetual struggle between capital and labour and believes that, after the ravages of Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and globalisation, and the anti-establishment anger that produced Donald Trump and Brexit, the argument for unions and collective bargaining is as vital as ever. Which brought him to The Deuce, his ambitious new HBO series charting the rise of the porn industry in 1970s New York.

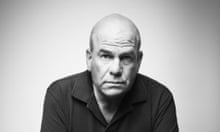

“What I stumbled into seemed to be a ready-made critique of market capitalism, and what happens when labour has no collective voice, and that seemed to be apt for this moment because I think a lot of the lessons of the 20th century are going to have to be learned all over again thanks to Reagan and Thatcher and all the neoliberal and libertarian argument that has come after,” says Simon, 57, unfailingly intense as he leans forward on a sofa.

The Deuce, a title derived from local slang for 42nd Street, sets up a colourful canvas of characters – hustlers, pimps, sex workers, morally exhausted police officers – in a sordid Times Square of graffiti, trash, neon lights, rising crime and sex shops. James Franco plays moustached twins: Vincent Martino, a savvy barman trying to keep on the straight and narrow, and his brother Frankie, a hot-headed scoundrel running up gambling debts. Maggie Gyllenhaal is Eileen “Candy” Merrell, a fiercely independent call girl who spots an opportunity in X-rated films. Porn is more profitable – and seemingly more liberating – than hanging out on street corners: this is the birth of smut on an industrial scale.

Simon continues: “There was always a market for prostitution, and even pornography existed below the counter in a brown paper bag, but there wasn’t an industry; that had yet to find its full breadth in terms of the American culture and economy, but we all know what was coming.

“It’s now a multibillion dollar industry and it affects the way we sell everything from beer to cars to blue jeans. The vernacular of pornography is now embedded in our culture. Even if you’re not consuming pornography, you’re consuming its logic. Madison Avenue has seen to that.”

Simon also has a lot to say about pornography. Whereas his critically lauded The Wire was ostensibly about the drugs trade in Baltimore but subliminally about race, The Deuce could be seen as ostensibly about the sex industry in New York but subliminally about gender.

Pornography “affected the way men and women look at each other, the way we address each other culturally, sexually,” he says. “I don’t think you can look at the misogyny that’s been evident in this election cycle, and what any female commentator or essayist or public speaker endured on the internet or any social media setting, and not realise that pornography has changed the demeanour of men. Just the way that women are addressed for their intellectual output, the aggression that’s delivered to women I think is informed by 50 years of the culturalisation of the pornographic.”

He admits: “I don’t have any real way to prove that, but certainly the anonymity of social media and the internet has allowed for a belligerence and a misogyny that maybe had no other outlet. It’s astonishing how universal it is whether you’re 14 or 70, if you’re a woman and you have an opinion, what is directed at you right now. I can’t help but think that a half century of legalised objectification hasn’t had an effect.”

The series is a collaboration between Simon and novelist George Pelecanos, described by Esquire as “the poet laureate of the [Washington] DC crime world”, who also had a hand in The Wire and Treme. Pelecanos has previously written about Hispanic sex workers trafficked on the same trail as drugs and guns.

“Personally, I think pornography has had a crude effect on society,” he says. “I’m a first amendment [freedom of speech] guy but I really feel it’s kind of like racism in the last few years: we’ve had a wake-up call because everybody thought, ‘Wow, it went away’. Same thing with misogyny, right?”

Pelecanos, 60, thinks about the two sons he raised and the conversations he overheard when their friends came to the family home. “The way they talk about girls and women is a little horrifying. It’s different from when I was coming up. It’s one thing what was described as locker-room talk, like, ‘Man, look at her legs. I’d love to…’ – that kind of thing. But when you get into this other thing, calling girls tricks and talking about doing violence to them and all that stuff, I’d never heard that growing up, man. I just didn’t.

“I think the culture’s changed because of the way women are depicted in popular culture. Pornography’s a big part of that. You can say nobody’s getting hurt, it’s just a masturbation fantasy and all that stuff, but these women are trafficked, man.”

He believes there is a through line to Trump’s stunning victory in last year’s presidential election. “There’s no doubt if Hillary Clinton had been a man, she would be president now. The code words that were used against not just her but female journalists and everybody that was involved peripherally in the campaign was awful. Never seen anything like it.”

Whereas Simon was seized by the convulsions of capitalism, for Pelecanos there was the attraction of gritty, graffiti-strewn Manhattan as seen in 70s movies such as The French Connection, Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, and blaxploitation flicks including Black Caesar and Shaft. His noir novel King Suckerman is set in the Washington of the day.

“That’s sort of my era,” Pelecanos explains. “I was a teenager in the 70s so you remember that better than anything. The texture of those movies, they felt really real, mainly because in Taxi Driver [Martin] Scorsese basically puts the camera operator in the back seat of the taxi and just shoots over his shoulder. There’s no lighting, there’s no costumes, there’s no picture cars. He’s just shooting what there is. In Mean Streets, they didn’t have to do anything but point the camera outside and get everything.

“We had to build everything and find the cars and the costumes, but it’s cool, man. I mean, we wanted it to look like a movie that got found, that was made in ’71, put in a vault, and somebody pulled it out and said: ‘Look what we got.’ When you look at the pornography scenes, they’re kind of starkly lit, as it is on a film set, and it’s not beautiful: it looks like work or boredom, even. Not to say somebody’s not going to get titillated – they probably will – but we didn’t want that and we didn’t try to do that. It is a challenge because you can’t not show it. Then you’re erring on the other side; you have to show what you’re talking about.”

Mad Men set the bar for period detail with its evocation of 60s New York interiors. The Deuce is as fastidious about haircuts and fashions and, with some help from CGI, transformed the New York neighbourhood of Washington Heights into the tawdry Times Square of the 1970s when it was caught partway between the early 20th-century glamour of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and the Disneyfied tourist plaza of today.

The New York Times observed recently: “The most consequential character may be the city itself, a New York two generations removed, which the creators and their team have captured through spot-on dialogue, time-specific set designs and atmospherics evoking The French Connection and The Taking of Pelham One Two Three. No bike shares, no artisan coffee, no sushi; you took the damned subway, you drank bad deli coffee – and if you wanted fresh tuna, you went down to the pungent Fulton fish market before dawn.”

Not that the experience made Simon nostalgic for a pre-gentrification, pre-hipster age: “There are things that have gone wrong now that are a different kind of wrong, in terms of people being priced out of neighbourhoods – Manhattan especially, but even some of the outer boroughs becoming a playground for the rich. But I don’t know if you can look back on what the lower-east side was like, the Times Square of the 1970s or the upper Manhattan, the Washington Heights of the 1970s, and think, ‘Oh man, this was a paradise.’ There were profound problems of dispossession and crime and pain, there were people who were asking the question in the late 70s: can New York survive?”

It is not by chance that a cinema glimpsed in the first episode is showing The Omega Man (1971), a post-apocalyptic movie in which Charlton Heston plays the lone survivor of a plague. By the mid-70s, New York was in a fiscal slump – immortalised in the Daily News headline: “Ford to city: drop dead” – and violent crime was rife. The sexual revolution, and changes in the legal definition of obscenity, helped throw prudishness to the winds and bring sex and commerce together in a hive of peep-show stalls, live sex shows and teenage prostitution. Is it a coincidence that this is the time and place where Donald Trump grew up and forged his business career?

Simon says drily: “Growing up is a phrase I would not use about the president of the United States. I don’t know where he grew up. I have no explanation, I have a million explanations, for this man and what he lacks as a human being. Certainly he’s misogynist and his understanding of sexual equality is minimal and he’s drawn to him an incredible reservoir of anger against women and against people of colour. There’s a lot of anger out there in American society; he’s drawn all of it to him and he’s weaponised it. It’s interesting.”

Asked what the 2016 presidential election told him about America, Simon replies: “It said to me 25 to 30% of our population is foolish and untrustworthy and incapable of self-governance, and that a demagogue in the right circumstances with the right amount of manipulation can go a long way. It also said that for all of her flaws, and she was not a perfect candidate in any sense, a much more plausible female candidate was at that moment in time problematic for America. We demonstrated a distaste for the idea of a woman president that transformed a lot of votes. I certainly woke up in a different America from the one that I thought I was in.”

His comments bring to mind the way Trump lurked behind Hillary Clinton during one of their presidential debates. She has subsequently written how the episode made her “skin crawl” and wondered if she should have told him: “Back up you creep, get away from me! I know you love to intimidate women, but you can’t intimidate me, so back up.” Trump’s campaign rallies regularly featured material referring to Clinton as a “bitch”.

Simon notes that Clinton received nearly 3 million more votes than Trump last November, only to lose the White House because of the quirks of the electoral college. “I certainly don’t think he represents the aspirations of the United States of America, but he certainly got enough votes that he gets to play at that.”

Simon is a former reporter on the Baltimore Sun and his Twitter account still describes him as a journalist, along with author and TV writer/ producer. He frequently bashes Trump on the medium. Recently, after the president criticised the media as dishonest and divisive, Simon tweeted: “Having metastasised white extremists and demonised a free press, @realDonaldTrump is ensuring the murder of working reporters in US is next.”

But the paradox of Trump is that major media organisations are galvanised in their work and booming in terms of readers and viewers.

“I think high-end journalism has been given a second wind,” Simon agrees, “primarily because of the direct attack on press freedoms that this administration has engaged in. Whatever existential crisis came to journalism from having mismanaged its revenue stream, I think, has been overcome by the fact people at the New York Times and Washington Post and mainstream media, Mother Jones, ProPublica, a lot of the core institutions in journalism, now know exactly why they’re there and what their job is.

“Were there any errors in terms of how television particularly allowed itself to be used by a demagogue during the election? Absolutely. But from late in the election cycle to the present moment I think there’s been a lot of good, aggressive journalism that has in some very basic ways been assertive for democratic values. The problems of the revenue stream in regional journalism – in municipal and state coverage – still exist. And we haven’t resolved issues of the revenue stream and the internet, but I would say if you didn’t know why you were still a reporter before November, you do now.”

Among the innumerable things that Trump has upended is a project that Simon was working on with his childhood hero, Carl Bernstein, who with Washington Post colleague Bob Woodward exposed the Watergate scandal that brought down president Richard Nixon. “The piece is based on his insight that while the presidency is still the presidency, and the supreme court is still the judiciary, it’s the legislative branch of American government that has become dysfunctional, has become purchased by capital, and it can’t function, it can’t do its job any more. Carl’s argument was: that’s where the drama has to be. We have to find a way to tell that story.

“We had to throw out 60-65% of the construct of the world when Trump won. When we wrote it, we’d presumed that either a mainstream Democratic party functionary or Republican functionary would win, so either a [Mitt] Romney type or a Clinton type. It did not presume an insurgency that was going to weaken both political parties and win. So the decision was made – we’d better shoot this after the election, make sure, and then, as the election happened, it was clear that whatever else we’d done we’d saved HBO about $12-14m of what would have been wasted money.”

Simon, Bernstein and co-writers Ed Burns and Bill Zorzi have since met to restructure the show and work out how to keep it relevant to the political moment. Evidently Simon is as hungry as ever, 15 years after The Wire, which still seems certain to be in the first paragraph of his obituary.

“I don’t have any resentment towards The Wire,” he says briskly. “I’m proud of that work and it has allowed me and the people I work with to do other work that might not have been greenlit had The Wire not been a success.”

Could The Wire be made today and look more or less the same? In 2015 the death in police custody of Freddie Gray, an African American, sparked widespread unrest in Baltimore. The murder rate is now the highest in the city’s modern history.

“There was a brief moment where I thought the drug war was going to be ratcheted down in Obama’s last term, when they started to actually address mass incarceration and the drug prohibition, but [attorney general] Jeff Sessions has seen to that, hasn’t he, at least on the federal level. So probably we could make the show similar. Would there be some emphasis on some other things? Probably.”

Although highly regarded in his field, Simon is no TV addict. He loves The Sopranos (“excellent work”) and admires Deadwood, The Handmaid’s Tale and the Canadian series Slings and Arrows, but has not seen Breaking Bad or Mad Men. Nor has he succumbed to the craze for Game of Thrones: “I have a cousin who’s read the books. He tells me you’ve got to read the books first. I’ve heard it’s excellent.” Instead he spends evenings reading – he’s currently researching the Spanish civil war – or watching baseball.

“I tend not to watch shows until they finish and then somebody will come to me and say, ‘No, no, they knew what they were doing, they knew where they were going’, and so I’ll be sticking in DVDs or downloads two years after something’s on the air. It’s certainly hypocritical when I guess I’m asking people to watch my television shows in real time. But nothing’s worse than giving eight hours, when you could have read a couple of books, to find out, boy, that was a great idea but those guys really didn’t have a plan… so I end up taking the guesswork out of it by being late to everything.”

The Deuce came about when an assistant location manager from Treme told Simon and Pelecanos about a man he knew in New York, a veteran of the old 42nd Street cesspool. “He kept saying, ‘You gotta meet him, you gotta hear these stories’, and George and I were very ambivalent because the idea of doing a show about pornography and prostitution seemed gratuitous. Since the advent of premium cable, when they got rid of the advertisers, there had been a lot of porn pilots that had gone nowhere and, in our view, rightly so.”

But one afternoon in New York they agreed to meet the man, learning that he and his twin brother had once been mob fronts for the bars and massage parlours of yore. “After two or three hours listening to him tell stories, George and I pretended to go take a walk and have a smoke – although neither of us smoke – and I said to George, ‘My God, I think we’re going to have to write a pilot here, I think we’re going to have to do something with this. This is amazing material.’

“The characters, the world and some of the themes that began to emerge, that really appealed to me in terms of labour and capital and the product being itself the labourer: flesh is the commodity here. And how the money and the power array themselves and how they don’t. The more we talked, the better it got, so we started to think that we might be able to do it in a way that wasn’t gratuitous, and that led to a lot of discussion and eventually we took a shot at a pilot and trying to world-build.”

Simon continues: “It felt like we were starting in on it just from this guy’s stories about Times Square, which is this physical plant where a lot of the industry began. It felt like we had something by the tail, but the more you think about it, the more we asked him about what happened to this character, what happened to her, what happened to him. These were the people who were there at the beginning, who were experiencing this moment where it went out to the greater world.

“The answers he gave us were never: ‘She married a podiatrist and she lives in Scarsdale and she has two kids and a garage.’ The answers were always attritive and painful. Now you’re dealing with something that’s not a lighthearted romp through the sex industry. Now you’re getting into the guts of something that is interesting. So the guy’s stories were compelling, the characters he was describing for us were compelling and the outcomes were telling.”

Simon and Pelecanos went on to consult porn stars, police, waiters, lawyers and journalists from the era, acquiring other stories on the way. They hope to be recommissioned for a second and third series that will take the story into the mid-80s. The mission, of course, was to humanise the protagonists – including the pimps and porn stars – and render them with their own distinct voices and personalities. They were determined that, despite personal misgivings about the coarsening effect of pornography on society, they would maintain a dispassionate reporter’s eye and not get into the business of preaching. Early reviews suggest they have succeeded.

Simon explains: “We were not particularly interested in having a heightened moral debate over the worth or utility or damage from drugs in The Wire – that’s not what The Wire was about. Certainly I think the use of illicit drugs is on the whole destructive to individuals and to society, but the war against them I think is infinitely worse and doesn’t in any way mitigate the damage from drugs. I was much more interested in how power and money array themselves around the drug war and around the industry of illegal drugs.

“The same logic applies in The Deuce, which is much less interested in having a discussion about whether pornography is good or bad or prostitution is good or bad. I accept these things as the given in the human condition. Now, if they’re going to exist, where does the money go? What happens to labour? Who profits? How does the society as a whole array itself to acquire that profit or to participate in it or to acquire the product? These things were way more interesting to me.

“Once you allow the moral question to dominate the narrative then I think you end up with a stunted argument and there’s only so much that can be said. On the other hand, if you follow the money and power and you see who’s attrited and who’s exalted, then you have a much more interesting story.”

Simon, after all, pushes his audience hard and does not deliver answers neatly tied up with a ribbon. “In 1971 a 12-year-old kid had to hope to steal his father’s Playboy magazine from under the mattress and even then it was a much tamer version of anything pornographic in the modern sense: you couldn’t figure out the facts of life from the centrefold. Do I think we’re better or worse off nowadays when a 12-year-old with a couple of keystrokes can access the entire construct of human sexuality right down to every misogynist fantasy, that that can be fed into a 12-year-old brain? Probably not a good thing.

“But I’m not sure how you make a narrative out of that and address all the others factors, which I think if you’re going to do anything, have to be attended to. I think in some ways you can get lost in either being too puritan or too prurient in this piece and what you have to do is basically attend to the why, the why of how this comes to be. That’s what makes it a grown-up story.”

The Deuce starts Tuesday 26 September on Sky Atlantic and NOW TV

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion