Looking for women’s stories of 19th-century miscarriage, historian Shannon Withycombe expected to find grief. Instead, she encountered startling admissions of joy at the knowledge of pregnancy loss, with women writing sentences like: “I am happy again”; “O Bliss, O Rapture unforeseen!” To a 21st-century reader only recently accustomed to reading writing by women who have broken a general cultural silence on the topic in order to discuss their experiences with miscarriage—experiences characterized by sadness and mourning—reading evidence of this kind of happiness feels strange and a little uncomfortable. That foreign feeling persisted as I made my way through Withycombe’s intriguing book, Lost: Miscarriage in Nineteenth-Century America.

There were many reasons why 19th-century women might have welcomed a miscarriage. The women whose thoughts Withycombe can partially access, by dint of diary and letter, lived with limited access to contraception and experienced adult life as a series of unending pregnancies. (Withycombe describes the condition of 19th-century womanhood as “twenty or thirty years of constant pregnancy, birthing, and nursing.”) Women especially expressed thankfulness at the ends of pregnancies when their families were in perilous financial circumstances, or when they were living in frontier conditions.

One of the women in the book, Alice Grierson, physically separated from her husband in 1871 when their seventh child died at 3 months old. In a letter to him, she left a description of her relationship to reproduction that makes it clear how exhausting many women found the endless births:

Charlie’s existence I accepted as a matter of course, without either joy or sorrow. Kirkie’s with regret, for so soon succeeding him. Robert came nearer being welcomed with joy, than any other. Edie was gladly welcomed so soon as I knew her sex … Henry succeeded her too soon to give me as much rest as I would have liked … and told you before he was a year old, that I would rather die, than have another child, yet no sooner was he weaned, than Georgie came into life … I firmly believe it injured me, as soon as I weaned him, and was again immediately pregnant, my nerves became so irritable to such a degree, that life has ever since, been nearer a burden to me.

Grierson told her husband she left his house because she feared getting pregnant again so greatly: “Both of us will know one thing, which will inevitably occur, if the good Lord permits us to meet again, and are both well aware of the possible consequences that follow.” Withycombe writes: “I was well aware of the numbers and had heard the statistics” about family size in 19th-century America, “but Grierson’s letter makes the lived reality clear.” If even Grierson, a good 19th-century mother, preferred complete separation from her husband to another pregnancy, it stands to reason that miscarriage would carry a different set of meanings for a woman in this situation.

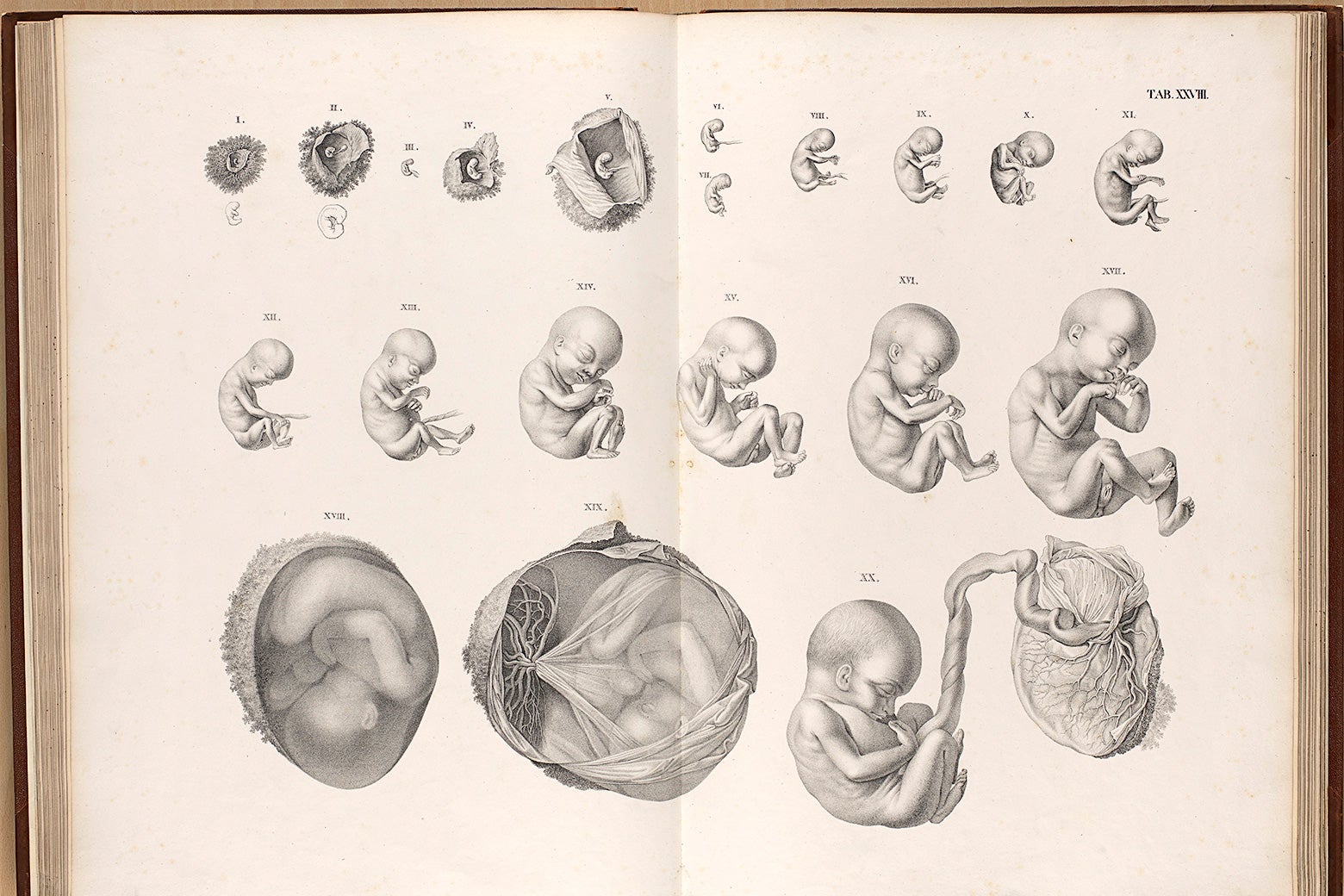

Then there’s the fact that many 19th-century miscarriages, in the age before medical imaging and consistent prenatal care, happened with much less fanfare. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, doctors were deeply confused as to what “counted” as a miscarriage, and most women didn’t consult those doctors in matters of pregnancy anyway. Withycombe quotes a series of books published in 1749 by German physician Johann Storch, who had a not-so-great handle on what came out of a woman’s body in the course of miscarriage: “Bubbly lots”; “untoward matter”; “fleshy morsels”; “useless beings.” This indeterminacy—was what happened a miscarriage, or just a very delayed menstruation?—may have resulted in women holding their early-stage pregnancies at emotional arm’s length.

Nor did they know much about the causes of the event, and this lack of knowledge allowed them a certain latitude to not worry. As late as the 1870s, Withycombe writes, a doctor published a prodigious list of potential miscarriage causes:

Among his almost seventy distinct causes he included: hemorrhoids, cancer, fissure of the rectum, drastic cathartics, fecal worms, bladder stones, lactation, the pain and shock of tooth extraction, syphilis, excessive sexual intercourse, ovarian disease, gastric irritation, chronic vomiting, coughing, sneezing, scrofula, debility, lead poisoning, anemia, small- pox, fever, morbid state of the placenta, falls, blows, overexertion, jumping, riding, lifting heavy loads, excessive joy, grief, rage, sorrows of captivity, and apprehension of death.

None of these miscarriage causation hypotheses seemed to have gotten through to the women whose diaries and letters Withycombe read: Only one mentioned the idea that something she did could risk the termination of a pregnancy. Withycombe theorizes that the very length and diversity of the list of possible causes might have rendered this particular bit of medical advice moot. In other words, realizing there was nothing they could do to avoid all these risk factors, women shrugged, threw up their hands, and carried on with their lives.

Withycombe finds that, following the cultural tradition of their day, the women whose diaries she examined didn’t necessarily think of their miscarried fetuses as people. “For many women,” Withycome writes, “pregnancy did not make a child—birthing did.” This wasn’t universally true—Withycombe does find some examples of women who perceived their babies vividly; Lucy Garrison wrote a letter in 1866, calling her fetus “Katherine” and writing “the child has hardly left me room for a word, what a talker at so early an age!”—but the modern idea that a woman would intimately “know” a fetus and consider it a person, from conception on, was not at all commonplace. In a terrifying and intriguing chapter, Withycombe describes how doctors attending miscarrying women in the second part of the 19th century, as embryology advanced and scientific attention turned to the fetus, got hold of miscarried fetuses to study. Sometimes doctors did this via trickery (those stories are extremely upsetting), but sometimes they came away with a fetal specimen with full consent from the woman and the family, for whom it simply had no emotional weight.

A final reason why miscarriage didn’t always inspire sadness lies in cultural expectations. Even in the late 1800s, as mainstream culture increasingly considered motherhood to be the ultimate expression of womanhood, women didn’t necessarily see miscarriage as failure. This was what Withycombe describes as a “space of freedom” in a generally oppressive patriarchal vision of women’s lives. As “doctors, politicians, and popular writers informed women that their sole duty in life was to have children, and their lives should be shaped around that undertaking,” the experience of miscarriage stood apart: “when that enterprise failed in the form of miscarriage, no one blamed the woman, least of all herself.”

Today, when we tend to have much more control over our own fertility (political climate and personal circumstances depending), the dominant narrative is that miscarriage is a loss. The struggle lies in claiming the experience publicly and owning a woman’s right to grief. Looking at this history reminds us that emphasizing this side of the miscarriage experience has its own traps. In a post about her research on the blog Nursing Clio, Withycombe writes: “It is dangerous to think that miscarriage is now somehow imbued with certain natural and inalienable meanings as a death, a tragedy, and something gone wrong.” Coercive laws requiring the burial of miscarried and aborted fetuses are the dark side of this perception.

Sometimes, looking at a diversity of women’s historical experiences can help us see how much we reduce and conflate women’s lives today. Reading the journal of Gertrude Thomas, in which the Georgian described her feelings relating to each of her 10 pregnancies, Withycombe points out: “Her writings reveal how each of a woman’s pregnancies could be differently construed”—a completely obvious statement that is revelatory when you think about how much pregnancy gets reduced into a universal experience in 2018. Why shouldn’t we believe that a mother like Gertrude Thomas or Alice Grierson could want one pregnancy, but not the next? Historically, and today, the particular circumstances of women’s lives matter.