Nobody likes to fail. But women take failure particularly hard—studies have shown that women are so averse to failure that they don't apply for jobs unless they feel 100 percent qualified. This hesitancy is understandable: When they do fail, women are judged more harshly than their male counterparts. Men, on the other hand, throw veritable failure parties; they're more likely to embrace "what doesn't kill you …" and plow ahead.

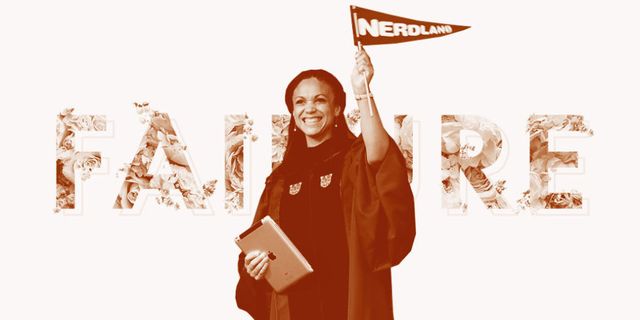

This week on ELLE.com, we've asked women to share their stories of failure. Not the kind of failure that led to some great business idea—just failure, plain and simple. We hope to shift the narrative about failure (it's ok! it happens!), or, at the very least, chip away at the idea that failure should be shameful or a secret. So here's to failing, loudly and proudly. Read more here.

This column was due to my editor last Wednesday. I failed to make the deadline. To be fair, I was dealing with unrelated incidents that included a dozen police cruisers, 150 wedding guests, major surgery, and a long-distance child care crisis, so I am not sure I should categorize missing a deadline as failure. Maybe it was more of an imperfection than full-fledged failure. I know the difference. At 42 I have amassed quite a track record of failure.

I got a D on my sixth-grade science project because I was just too lazy to do a good job. In eighth grade, I campaigned hard to be president of student government, but I lost the election. I spent nearly a decade torturing school orchestra conductors before one told me I was a failed cellist, and if I truly loved the instrument I would cease playing it. What happens when I try to speak French can only be described as failure. In college, I cheated on my very cute, kind, and smart boyfriend during my sophomore summer with a guy who was not kind or smart or particularly cute. Fail. My first marriage ended in divorce five years after it began. Divorce does not always indicate failure, but mine did. We were parents of a very young child, our problems were minor, and we should have worked harder to overcome our immaturity and selfishness. We failed with lasting consequences.

I am no rookie when it comes to failure, but during the past decade, my failures have been more spectacular because they have been more public. Once I began to pursue part of my professional life firmly within the public realm, I abdicated a luxury I had not even realized I previously enjoyed—private failure. It is not as though I suffer Kardashian-level scrutiny, but I have been on the receiving end of mean-spirited needling and bloodthirsty frenzies after minor stumbles and serious screw-ups. Public failure by women is gourmet fare for trolls.

While reading a teleprompter on live television I mispronounced the Marine Corps motto Semper Fi. It is short for the Latin semper fidelis, meaning always faithful, and is pronounced with a long i. Like any good nerd, I took high school Latin, so I know all of this. But, for some reason, what came out of my mouth was not Semper Fi but instead, Semper Fee. Fail. This is the Marines I was talking about, not some '70s band. The hate mail came fast and furious. Not only was my intellect questioned, but my patriotism, too. How could I not know such a thing? What kind of ridiculous, liberal, pseudo-intellectual excuse for a journalist was I? Some people even took the time to send me bound histories of the Marine Corps and elementary Latin textbooks.

Public failure is altogether different, particularly if the failure is more substantive than a mistaken pronunciation. I spent four years engaging in bi-weekly, two-hour conversations with guests about sensitive political topics as the host of my own television show. To do that kind of work with any kind of vulnerability and honesty is to invite opportunities for failure. I once yelled at a contrarian guest. I still believe every word of what I said to her, but I am not proud of having expressed myself with such rage. I once allowed a panel that was supposed to be humorous to become hurtful. I still believe no one had malicious intentions, but I am still sick about any pain we caused. And I cringe at how horribly I butchered the names of many of my guests. I will never repay the cosmic debt I owe because of how awkward it was when I inaccurately introduced so many smart and interesting people.

And then of course there is the very public end of the show itself. I am still not sure whether to categorize this as a failure. The trolls would have me believe it is. They dance merrily on Nerdland's grave and gleefully celebrate my having been "fired." The truth is predictably more complicated. I left on my own terms and with a social media flourish that still causes me to publicly sing some Beyoncé lyrics louder than is probably dignified. But when former viewers tell me how much they miss the show, how much they wish we were there to help them navigate the complicated 2016 election cycle—on those days I feel the sting of failure. Those moments feel as though I failed my audience and my team, and it is still so fresh, immanent, and new. I do not yet have insight or distance, just tears and silence and the determination to find another path. Because what else is there? Sometimes we fail.

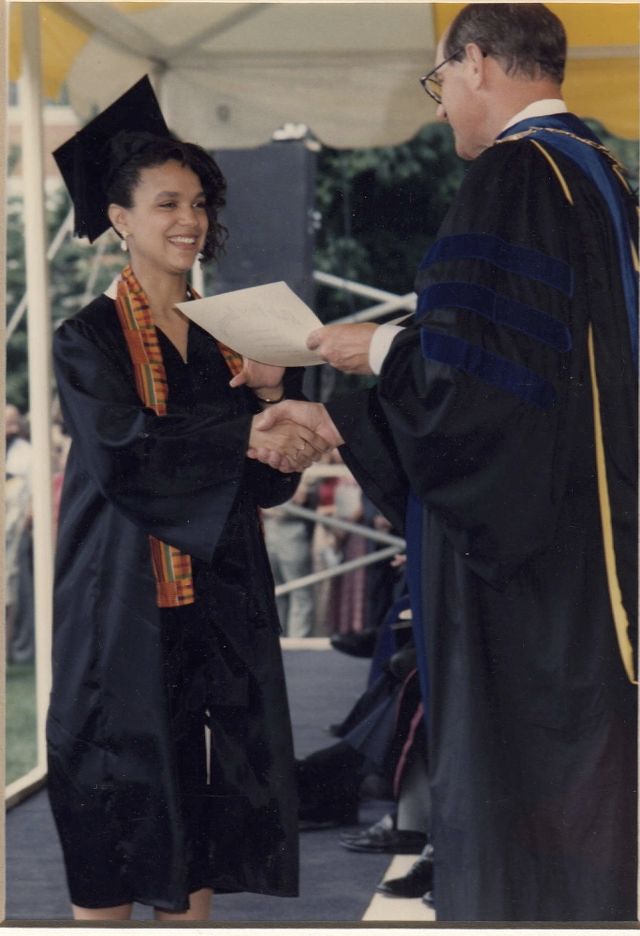

These are my failures. I own them. Still. I try to remember that these are things I did, they do not represent who I am. I try to allow myself to feel guilty, without slipping into feeling ashamed. Guilt about our failures can be an adaptive emotion, one that motivates us to do better in the future. I hated how it felt to get a D on that sixth-grade science project, especially because I knew I deserved it. That D is a big part of the story of why I became an academic overachiever. I probably graduated Phi Beta Kappa because of that D. Thanks Mrs. Gill. The same is true of the failure of my first marriage. Divorce was so paralyzing painful it nearly cured me of the desire to commit altogether, but the guilt surrounding that failure has value as well. Although I cannot speak for him, I hope the man to whom I am now married finds I am a better able to love because of the lessons I learned failing the first time.

I try not to deny my failures. I try to acknowledge them, but also to hold them at a bit of a distance, because I know what happens when you bring them in too close. Held too tightly, failure shifts from guilt to shame. Guilt is motivational. Shame is corrosive.

Shame exists in response to some real or imagined audience. It is not just about violating our internal moral guide. Shame arises when you transgress a social boundary—one that may or may not have any relevance to you. And while guilt is specific, confined to a certain event or series of events; shame is global. It causes us not only to evaluate our actions, but to make a judgment about our whole selves, taking a single incident and making it an evaluation of our whole identity. Shaming is what the trolls try to do on social media. It is not just a mispronounced word; it is a judgment about my intellectual capacity, my membership in the community, and my worthiness to speak on matters of political and social life. They suggest I shouldn't just feel guilty for a single failure and motivated to do better next time; they want me to feel ashamed of who I am at my core.

Shame produces what psychologists refer to as a belief in the malignant self: the idea that your entire personhood is infected by something inherently bad and potentially contagious. Shame can bring with it a psychological and even physical urge to withdraw from others. Sometimes shame leads to inappropriate levels of submission or appeasement because we want prove ourselves worthy of love and respect. When we feel chronically ashamed, we tend to attribute all negative events to our own failings. Instead of seeing the world as capable of producing both good and bad outcomes, we see ourselves as ourselves worthy of punishment. Shame eats away at self-esteem. It is healthy to acknowledge you fail. It is toxic to believe you are a failure.

Parsing the distinction between being a person who fails and being a failure can be difficult, iterative work. Part of the challenge for me is rooted in surviving sexual assault by an adult neighbor when I was 14. There are things predators say to victims to make us believe our suffering is a result of our own failures. These words become tapes we replay with frightening efficiency long after the attacker's voice is silent. One need not be a survivor to struggle with shame. For girls and women, who are socialized to draw our sense of self from our friendly, familial, and romantic relationships, we are more likely to experience failure as social and global, rather than individual and specific. We are more likely to feel shame than guilt.

My own best tool for acknowledging failure, while keeping a bit of perspective are stacks 8 x 6 spiral notebooks. I have been keeping them as journals since I was 11 and read Anne Frank: Diary of Young Girl. I was convinced that even though my adolescence was not set against the horror of the Holocaust, keeping a record of my ambitions and accomplishments would be inspiring. Turns out my journals are mostly full of my perceived failures. They are remarkably consistent. I am perpetually trying to lose 15 pounds, pay off debt, and get over some boy. I have been writing for three decades. I have varied from a size 4 to a 14. I have earned between four figures and seven in a single year. I have been single, engaged, married, divorced, and remarried. I have earned a PhD, written two books, hosted a national television show, had two beautiful daughters, lived in some of the nation's greatest cities, interviewed world leaders, and realized dreams I didn't even dare to dream at 11. All the while I am trying to lose 15 pounds, pay off debt, and deal with heartache.

How wonderfully human I am. Not a failure at all. Just a girl who fails even as she slays.