Illustration: Elena Scotti/Jim Cooke, Photos: Shutterstock/Getty

When the White House affirmed November as National Adoption Month, it released a largely anodyne presidential proclamation. “Adoption is a blessing for all involved,” the proclamation read, adding that adoption “affirms the inherent value of human life and signals that every child—born and unborn—is wanted and loved.”

By invoking the unborn, the Trump administration positioned adoption as an alternative to abortion. It is a familiar right-wing tactic; during 2016’s vice presidential debate, Mike Pence crowed over transforming the rhetorical tic into policy. “The state of Indiana has also sought to expand alternatives in healthcare counseling for women, non-abortion alternatives,” Pence said. “I’m also very pleased of the fact that we’re well on our way in Indiana to becoming the most pro-adoption state in America.”

“Adoption gets imagined as this ‘third option’ for pregnant women,” says Kate Livingston, a gender studies lecturer at the University of Indiana Bloomington, who is also a birth mother. In popular discussion, domestic infant adoption lies directly between the politically fraught poles of abortion and parenting, often represented as a stigmatized, single, impoverished mother. And unlike abortion and parenting, this “third option” is commonly treated as an unqualified good—a gift from birth mother to adoptive families, an act of total selflessness, or a blessing for all involved.

Adoption is a blessing for countless people—a way of building families for LGBT couples, single parents, and those struggling with the immense pain of infertility, a desirable option for many women dealing with pregnancy, and a creator of loving homes for adoptees across the country. Perhaps, because adoption is so uncontroversial, it’s been slow to be included under the reproductive justice umbrella, even as intersectionality has gone mainstream and the terms of reproductive justice have broadened. Once narrowly concerned with abortion access, many feminists committed to reproductive rights are now also likely to examine issues like the maternal outcomes for black women, or the plight of pregnant people in prison. But framed as an idealized “third option,” adoption is neglected, treated as a win-win for birth mother and adoptive parents that somehow transcends the need for systemic analysis.

But adoption is a reproductive issue as thorny as any other; it is not a substitute for abortion, and accordingly has little place in the abortion debate. As writer, educator, activist, and adoptee Liz Latty points out, adoption is “not an alternative to abortion, it’s an alternative to parenting.” Instead, adoption is a reproductive justice issue in its own right, one that deserves to be examined from an intersectional perspective.

Adoptees, birth parents, and allied adoptive parents have been doing so for years. If, says Livingston, the broader understanding of adoption is “always going to be a response to pro-life, pro-choice politics,” then “you never get to see the reality of adoption on its own terms.”

Pointing to Scandinavia to illustrate the benevolence of a hearty welfare state is practically reflexive, but in her book Selling Transracial Adoption, sociologist and transracial adoptee Liz Raleigh raised a fascinating statistic: In 2016, just 41 Swedish couples adopted domestically. If Americans adopted domestically at the same rate, the nation would see around 1,300 such adoptions each year. Instead, American babies are adopted at a rate more than times 10 times their Swedish counterparts. In 2014, the last year from which there is data, there were 18,329 domestic infant adoptions in the United States. That’s close to the total number of similar adoptions across the whole of the European Union.

It’s clear that, in countries that value gender equality and have strong social safety nets, fewer women elect to place children for adoption. When, at the height of the international adoption boom, American families adopted en masse from nations like Ethiopia, China, and Guatemala, it was easy to understand that the availability of these children was directly tied to desperation and want in those countries. The language of reproductive “choice” favored in the United States—which depicts women as picking breezily through a buffet-style lineup of options—conceals the fact that many poor and marginalized women have very few meaningful opportunities for reproductive decision making. A 2016 Donaldson Adoption Institute survey of 223 birth mothers found four out of five of them citing financial and housing concerns among the primary reasons they placed children for adoption. “Choices” are constrained when a pregnant person is struggling to pay rent.

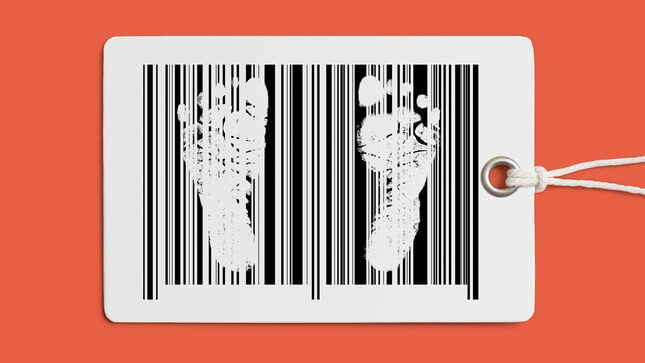

Descriptions of birth mothers (some of whom prefer the term “first mothers”) as women who give the “gift” of a baby to adoptive parents belies the fact that domestic infant adoption is a billion-dollar industry. A 2013 survey of adoptive parents found that the average adoption from foster care cost $2,612, while domestic infant adoptions averaged between $34,093 and $39,966.

Accordingly, adoptive parents skew wealthy and white. Across all types of adoption, including domestic infant adoption, international adoption, and adoption from foster care, a majority of adoptive parents are white and a majority of adopted children are not. This intersection of race and market forces has been the source of major controversy. National Public Radio reported in 2013 that “black babies cost less to adopt.” Since most adoptive parents are white and prefer same-race children, agencies often offer adoptive parents steep discounts—sometimes tens of thousands of dollars—to domestically adopt black babies.

The discounts aren’t just horrifically racist, they also incentivize families who might be reluctant to parent transracially to consider doing so purely out of dollars and cents pragmatism. In the wake of the controversy, some agencies have taken pains to conceal the practice. “They’ll use code words, like they offer a special grant for a ‘hard to place child,’” Susan Leksander, a therapist who serves as Adoption Agency Supervisor and First/Birth Family Specialist at the adoption alliance PACT, says. “The only thing that is differentiating them is that they’re a black child with two black parents. That is why they’re ‘hard to place,’” she adds. Agencies have implemented education for families who seek to adopt transracially, but this training can amount to a short seminar. “You can’t learn how to be a parent to a child of color in a half-day workshop,” says Leksander, who is both a birth mother and a transracial adoptee.

The conspicuousness that can come with transracial adoption places another burden on adoptees. “You get a lot of attention from strangers,” said Alice Stephens, author of the new novel Famous Adopted People, who’s a Korean-American transracial adoptee. People “feel like they can just come up to you and tell your parents how wonderful they are to have adopted you and tell you how lucky you are to have been adopted,” said Stephens. This sort of intrusive and condescending praise is a side effect of the panacean view of adoption, and according to Stephens, it can serve to suppress adoptees’ ability to be able to express their conflicting feelings about adopted.

As the “third option” perspective obscures the racial and market forces at play in adoption, so too does it obscure the life-long experience of adoptees and birth families. A 2007 survey found that 75 percent of birth mothers reported feeling grief and loss 12 to 20 years after their placement. And a majority of the women in the Donaldson Institute survey said they felt ambivalence or dissatisfaction about their decision, and wished that they’d had access to more information about raising their child.

Adult adoptees and birth families alike often describe themselves as reckoning with disenfranchised grief—a sorrow made all the more difficult to bear because it is not widely recognized as valid. As adults, adoptees can find themselves at increased risk for struggles with addiction and mental health, as well as attempts at suicide, even as their critiques of adoption are ignored in favor of a broader narrative that demands gratitude from adoptees.

“People want to believe that adoption creates good families,” said adoption scholar and transracial adoptee Kimberly McKee. There’s a “belief that if you rescue these kids, their lives are somehow going to be better. And no one wants to have that dream disrupted.”

At the heart of what Latty calls the “fairy tale narrative of adoption” is an unspoken assumption that some families are inherently more worthy than others. Take, for example, the adoption tax credit, which allows parents to recoup up to $13,570 of their adoption fees. It’s non-refundable, so the credit is of little use to the family building efforts of low-income people. But households with incomes up to $203,540 can claim the full credit, while families with incomes up to $243,540 can claim some portion of it. Households with an income of $200,000 represent the top six percent of American families. Meanwhile, the 20-year-long enterprise of shredding the social safety net on which poor families rely continues.

If you’re middle class, “the government will literally subsidize your family making project,” says Latty. “And if you’re marginalized, we’re actively making it impossible for your family to stay together.

There are policy solutions that might help ensure infant adoption is practiced as ethically as possible. Open adoptions, in which birth families and adoptive families maintain some degree of contact, are today the norm. But contact agreements are largely unenforceable, and many open adoptions eventually close. Some states have given birth parents and adoptive families the option of making their post-adoption contact agreements, or PACAs, legally enforceable, helping families who enter into an open adoption have more certainty that the adoption will stay open. Laws concerning the amount of time after birth that postpartum women must wait before signing adoption consent forms similarly vary. While 15 days must pass before Rhode Island women can place newborns for adoption, Kansans may irrevocably terminate their parental rights just 12 hours after giving birth. More than a third of the birth mothers surveyed by the Donaldson Institute said they wished they’d had more time to consider their relinquishment paperwork.

And prospective adoptive parents can try to ensure that they’re pursuing adoption through the most ethical possible means. Agencies that rely solely on birth mothers placing children have a vested business interest in persuading pregnant people to do so. But for other organizations, like PACT, adoption is not the only source of business. PACT offers wrap-around support services to transracial adoptees of all ages, and Leksander says the organization could stop placing children for adoption altogether and still stay afloat. Because of this, Leksander feels she can approach her work with pregnant women “without an agenda, without any sort of idea about what is right for them other than helping them come to an answer for themselves.”

PACT also calculates its fees on a sliding scale based on the income of adoptive parents, not the race of the child they’d like to adopt, with the goal of making adoption affordable to a broader swath of the population. The agency serves adopted children of color, and the educational program they require of adoptive parents is a months-long process. And because they invest in recruiting non-white families, most of their placements aren’t transracial despite the fact that all the kids they place are children of color. But changing laws and reshaping widespread adoption industry practice would require “tremendous political will and activism,” Leksander says. “Which is why reproductive justice needs to see adoption as part of its wheelhouse.”

It also needs to amplify the perspectives of adoptees and birth families, especially when they raise uncomfortable issues that challenge the prevailing adoption narrative. “Children are cute, children are acceptable. Everybody likes babies,” McKee notes. “When these babies grow into adults like myself, an adoptee who also studies adoption, we’re less cute.” The idea of adoption as “a blessing for all involved” is a narrative that serves ethically dubious adoption facilitators, while pulling double duty as an anti-abortion talking point.

Adoption narratives need to also make room for adoptees who say that adoption is a trauma, adoptees who watched #KeepFamiliesTogether trend on Twitter and cheered for the support rightly directed towards families separated at the border and yet wished more people would apply the same logic to avoidable domestic adoptions. “Adoptees are finding other adoptees and realizing that they can speak out,” Stephens says, “and that if they speak out together they have more power than if they’re just grumbling in the corner and people think they’re just ungrateful adoptees.”

“There is a tremendous resistance to hearing adoptee stories,” Stephens adds. It took her five years to publish her novel, which tells of a Korean-American transracial adoptee much like herself who heads to Korea in search of her biological mother. It sounds like an often-told story, but Stephen eschews cliche in favor of biting critique of simplistic adoption narratives. “I had so many rejections and I think it was just because people are really uncomfortable with the portrait of adoption that I give. They don’t want to face the fact that adoptees have their own stories.”

Americans might also broaden our perspective as to what a decent home looks like. The idea that it is a universal good for a child to be raised in a more privileged family hits at the heart of our national myth, suggested Raleigh. It’s a “tale of upward mobility,” she said. “Of rags to riches stories.” And of course, the loving, supportive families created by adoption are visible. The potential families that are lost are not, making them far easier to overlook and rendering invisible the grief of those who mourn them. Raleigh says that she tells her students that in adoption, “you cannot gain a child without someone losing one.” “That part,” she says, “oftentimes goes unaccounted for.”

Gabrielle Bruney is a writer and editor from Brooklyn, New York.