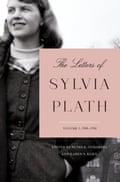

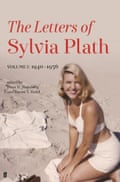

On the US cover of Sylvia Plath’s Collected Letters, a volume out this week that contains mostly unpublished letters by the poet between the ages of eight and 24, is a picture of her taken in December 1955. She’s walking outside somewhere in Cambridge, bundled up in a coat, and has a thoughtful smile. The UK edition went for a very different depiction of Plath, however: a full-colour photo of her on a beach in a bikini, blond and beaming – a visual antithesis to the ambitious, intellectual poet.

This is not the first time Plath’s image has been used to make her appear trifling or superficial. In 2013, Faber, the publisher of the bikini-lead UK edition, released a much-derided anniversary edition of The Bell Jar that showed a woman checking her makeup on the cover. Whatever symbolism intended was overwhelmed by the proto-chick-lit design; a story of an attempted suicide and subsequent hospitalisation is somewhat undermined by the focus on matching lipstick and nails. Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams, a collection of her prose, is also bedecked with the bikini shot, which the Telegraph also recently used to illustrate a story about her love letters. Plath’s volume in the Faber Poet to Poet series, in which a poet selects work by another they admire, sees her estranged husband Ted Hughes’s choices illustrated with a photo of Plath semi-undressed; and the biography Mad Girl’s Love Song, by Andrew Wilson, is covered with a blond, bare-shouldered Sylvia in profile, cropped to suggest a nude nymph.

These are the images that publishers think best represent Plath, an internationally recognised poet and novelist, an icon, an alleged victim of domestic abuse, a single mother, a person with mental illness and person who killed herself. Why is her work, so heavy with symbolism and myth, which documents the frustrating consequences of transgressive womanhood, marketed with so little thought and respect?

In answering this question, it is hard not to be cynical about the British literary establishment and its continued “protection” of Hughes. In the wake of her death, Team Ted went into overdrive to construct an image of Plath as a crazy, spoiled woman. Bitter Fame, the only authorised biography of Plath – which included so much interference from Hughes’s sister, Olwyn, that author Anne Stevenson eventually referred to it as a “work of dual authorship” – includes two appendices that eviscerate Plath, presumably to undermine or negate any praise that remained.

This is not a hysterical presumption. In her book Sylvia Plath and the Mythology of Women Readers, scholar Janet Badia writes about “tropes meant to disparage Plath’s fans, especially the young female readers among them, as uncritical consumers”. This, she argues, “has dictated the terms of Plath’s reception by the literary establishment and by popular media”. The curation of her image plays a role. Perhaps the rationale is that pictures of smiley Plath counterbalance the darkness in her work, lending extra tragedy to her illness and death. But this kind of correction is not made for male authors, no matter how dark their writing or interior lives. Consider Plath’s fellow confessionalists. Robert Lowell had manic depression and was hospitalised at McLean, in Massachusetts, where Plath was also treated in 1953 and which she immortalised in her novel, The Bell Jar. All his covers see him posed studiously, writing, reading, crucially able to keep his clothes on. Meanwhile, Anne Sexton, who studied under Lowell with Plath and also killed herself, receives the bathing suit treatment with her Selected Poems.

Presenting female writers as sexualised and frivolous diminishes their intellectual credentials, tarnishes their work as slight, not to be taken seriously. Plath’s poems were visceral and impolite; her novel was about madness. The image that best represents a writer of her range and talent is not, as she wrote about in her poem The Applicant, the “living doll” on biographies and collections and broadsheets “everywhere you look”, forever emblazoned on our consciousness as a 22-year-old bronzed blonde in a bikini.

Plath only had blond hair for about three months. She documented the phase in her short story Platinum Summer, another roman à clef in which her protagonist dares to “be a woman for a change … not a walking library stack”. But she discovers that “the worldly platinum-blond type” is incongruent with the true self she eventually reasserts by returning to her natural chestnut brown hair colour. In a letter to her mother on 27 September 1954, Plath admitted her “brown-haired personality is more studious, charming and earnest”. She was “happy” she went back to her natural hair colour, preferring to “look demure and discreet”.

We know brunette Sylvia was how Plath wanted to present herself. So while the new Collected Letters boasts that it is “unabridged, without revision” and presents the author speaking “directly in her own words”, selling an author, who liked her studious and demure self, with a cheesecake bikini shot undercuts any claims of dedication to authenticity.