Want Better Outcomes? Take a Hammer to Your Company’s Glass Ceiling

Dana Anderson, former chief marketing officer for Fortune 500 company Mondelēz International, said that when she first started her career in journalism, “it didn’t even occur to me I would make less than the men.”

It was the late 1970s and, working in an industry that women were flocking to, Anderson felt free from traditional business barriers that kept women from advancing.

“I thought, ‘Well, what could happen? I work hard. I’m a nice person.’”

But now after having worked on a profit and loss statement and getting a closer look at the inner workings of company finances, she said her rosy outlook was simply naive.

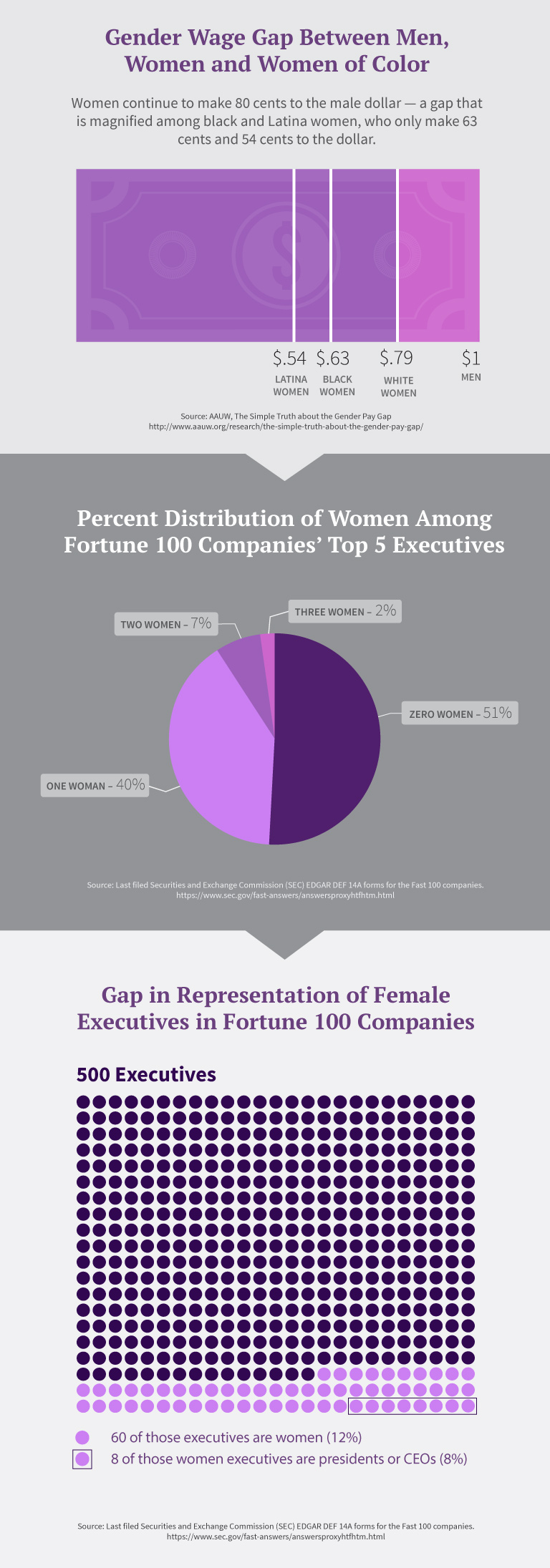

The American Association of University Women says that, almost a century after earning the right to vote, women continue to make an average of 79 cents on the dollar compared to their male counterparts—a gap that is magnified for black and Latina women. But the wage gap, which examines the differences in pay for the same work for employees in the same positions, likely understates the problem since men still rise higher than women in most companies.

Read the text-only version of this graphic.

Concerns over gender wage disparities and a lack of race and gender diversity in executive leadership can lead investors to lose confidence, motivating policy makers to lean away from transparent reporting practices. But experts argue that this move to thwart diversity initiatives is counterproductive and may ultimately hurt employee performance, derail innovation and negatively affect a company’s financial health.

“Companies should feel morally obligated to pay men and women the same,” said Anderson.

But when equality and profits don’t align, policy is what keeps businesses accountable.

Few women as top earners

One such policy recently came under fire when the Trump administration announced that it is blocking an Obama-era rule that required businesses with more than 100 employees to collect and report salary data by gender, race and ethnicity.

The now-obstructed Action on Pay Data Collection intended to close the gender gap by focusing on “public enforcement of our equal pay laws and provide better insight into discriminatory pay practices across industries and occupations.” The U.S. Chamber of Commerce voiced its support of retracting the policy, arguing that the reporting was burdensome for businesses, but the decision has been widely criticized by women’s advocacy groups who believe this is a setback for equal rights.

“They’re not so much afraid that collecting the data is costly, but how much it will cost to publish it,” said Julie Fox Gorte, senior vice president for sustainable investing at Pax World Management. “Just look at what happened in Europe after they were required to report.”

Earlier this year the United Kingdom established similar rules requiring companies with more than 250 employees to report wage disparities between men and women. As one of the first companies to release its report, public news broadcaster BBC faced backlash after revealing a significant gender pay gap and that only a third of their top earners were female.

But the diversity dilemma is global. Companies worldwide continue to struggle with gender representation at the top.

Having public representation is important so that people who are younger have examples, role models and a path to career success.

When examining 100 of the largest companies by revenue ranked by Fortune Inc., the trend is apparent. An analysis of Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings found that although these Fortune 100 companies are nearly closing the gender pay gap in dollar amount for CEOs, there continues to be a significant representation gap. Just 60, or 12 percent, of the 500 executives listed across top earners were female, and only 8 percent of those women executives were identified as president or CEO.

More than half (51 percent) of companies failed to report a single female executive in the list of their top five earners. And only 9 percent of companies reported more than one female executive, and none reported more than three.

Even so, 2017 is a record-breaking year for women’s leadership across Fortune 500 companies. This year saw the highest proportion of female CEOs in Fortune’s 63-year history, with 6.4 percent of companies run by women. But that’s not nearly enough to close the representation gap.

Natasha Thapar-Olmos, a licensed clinical psychologist and an assistant professor of psychology at Pepperdine University, said that “whether it’s conscious or unconscious, having so few women as the head of Fortune 500 companies sends the message that women aren’t successful here.” She said, “Having public representation is important so that people who are younger have examples, role models and a path to career success.”

The lack of representation in the top echelons of companies is why Gorte argues that influential companies may not be keen to transparently report comprehensive gender, race and salary information for their employees.

“Politically, the empowered group sees nondiscrimination as a threat,” Gorte said. “As investors, we think discrimination is actually a handicap for companies.”

“Companies are concerned with reputational risk,” she continued. “If investors lose faith in you, they can take your value down.”

Better for company performance

But ending public reporting on diversity metrics is a short-term solution to a more acute problem.

Kevin Miller, senior researcher at the American Association of University Women (AAUW), said that companies should have a vested interest in understanding and closing the gender wage and representation gaps.

“When people aren’t paid fairly, they are more likely to depart,” he said, “and turnover costs are extremely high for companies, especially in really skilled positions.”

Diversifying leadership and paying women an equal wage is simply better for employees and company performance.

White male executives are coming from a place of privilege, which means that they may not see from where they’re standing that there is a diversity problem that needs to be addressed in the first place, Gorte said. The “out groups”—women, blacks, Latinos—see and perceive the issue of disproportionate promotions and compensation across race and gender.

Having diversity around the table leads to more ideas, helping to narrow down on the best ideas and solutions.

Thapar-Olmos argues that when women see a lack of representation or feel they are being cheated out of fair pay, they don’t feel that they are a valued member of the company, inevitably compromising their performance at work.

Work environments affect performance, “and performance is tied to emotional health,” Thapar-Olmos said.

This lack of diversity within Fortune 500 companies can also hinder innovation and cause leadership to find the wrong solution to a problem.

“Although it may take longer to deliberate,” Thapar-Olmos said, “having diversity around the table leads to more ideas, helping to narrow down on the best ideas and solutions.”

Gorte said groupthink, a social psychology concept coined by psychologist Irving Janis, “tends to be an inhibitor in decision making…Groups that are homogeneous—whether that’s a group of Hispanic women, black men, white men—tend to be less effective, even if they have a higher IQ.”

Unless executive leadership is inherently motivated to address the lack of diversity—whether it’s gender, race or ethnicity—groupthink may continue to be the norm within companies led largely by white men.

The equal pay pledge

If driving down retention costs from losing skilled employees or investing in innovation isn’t enough reason, being proactive about closing the pay gap may save companies from costly lawsuits and public criticism later down the line.

As several Silicon Valley-based technology companies have recently learned, ignoring concerns about the pay gap and a lack of growth opportunities for women can lead to bad press, which may inevitably affect the market values that companies were initially trying to protect.

The AAUW’s Miller said the public outcry around gender disparities in business can help raise awareness for leadership and motivate them to address the issues sooner rather than later. He recommends that companies acknowledge “this is a problem and that fairness and equal pay [are] a priority.”

He said some companies have taken equal pay pledges and are taking a public stance on the need for fairness and pay equity, but that companies “can also go further.”

“One thing that a lot of model companies have done in this space is pay-equity audits,” Miller said. These companies “review the pay levels of their employees so that they can see relative to position, job tenure, education, qualifications et cetera.”

But in the end, without policy that forces companies to close their pay and representation gaps, the decision to conduct such an audit and close the pay gap for their employees is left up to individual companies.

Pepperdine’s Thapar-Olmos said, “If we remove that layer of accountability, we disincentivize business leaders and companies from attending to possible gaps in wages or discrimination.”

Without requirements to report those hard facts and figures, she continued, “there is no accountability or opportunity to address that.”

Citation for this content: OnlinePsychology@Pepperdine, the online clinical psychology master’s program from Pepperdine University.